06.09.2025

As housing costs rise in Boston, homelessness soars in the cities that surround it

Categories: News, Press Releases

06.09.2025

Categories: News, Press Releases

By Andrew Brinker, Globe staff, The Boston Globe

BROCKTON — In this former manufacturing hub 20 miles south of Boston, a growing number of men with shopping carts full of belongings sleep in tunnels beneath the commuter rail. People gather in the park across from a downtown shelter. Tents are tucked into grassy patches behind old factories and in roadway medians.

To some extent,homeless people have always existed in places like Brockton. But what’s happening now is different.

After a decade of decline, the number of people living on the streets and in shelters has risen sharply across Massachusetts over the past several years. Nowhere has that surge been more pronounced than in the midsized cities that ring Greater Boston, former industrial hubs that have long been affordable, if economically challenged, refuges for the working class. Now housing prices have surged, and by some measures, these cities are counting record-high rates of homelessness.

People gathered underneath the commuter rail tracks in Brockton on May 22. David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

“We’ve reached a critical mass in Brockton,” said City Councilor Winthrop Farwell. “Our city is at the center of what is really a societal crisis, and there is no good answer for how we’re supposed to go about handling it.”

There are many causes of homelessness. But local leaders point to one in particular to explain the recent surge: the soaring cost of housing.

As people priced out of Boston flock to places like Brockton, Worcester, and Lowell — attracted by their cheaper housing costs and accessible commutes — rents in those once-affordable cities are rising at a rapid clip. That’s bringing investment to cities that have long struggled to attract it, but it is also stretching longtime lower-income residents to the breaking point.

It’s a vexing cycle.

As encampments crop up, local officials are struggling to balance the needs of their poorest residents and the logistical, and ethical, problems their tents present.

“We do what we can to help as many people who need it,” said Jason Etheridge, president of Lifebridge North Shore, a Salem-based nonprofit that runs shelters and supportive apartments in several cities north of Boston. “There are forces in the economy that have made it much easier to become homeless. At a certain point, shelters can’t fix that.”

Before the past few years, Brockton had made significant progress on homelessness.

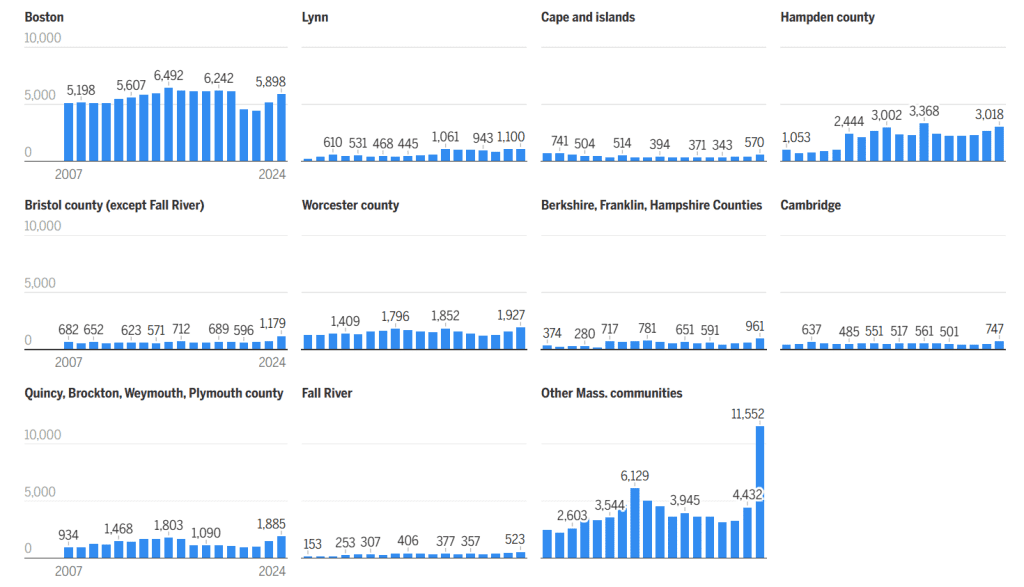

There is limited data counting homeless people in most municipalities, but in 2021, officials counted 943 in a federally designated area south of Boston that includes Brockton, Quincy, Plymouth, and Weymouth, the fewest since 2008. By 2024, that number had doubled to 1,885, the highest number since tracking began in 2005.

Homelessness in Massachusetts cities since 2007

The federal government measures homelessness through annual Point-in-Time counts of the homeless population, conducted one night each year by local officials. Communities are grouped into Continuums of Care, which are regional or local planning bodies that coordinate housing and homeless services funding.

Chart: CHRISTINA PRIGNANO/GLOBE STAFF Source: US Department of Housing and Urban Development Point-in-Time estimates of homelessness

The trends are similar in Fall River, New Bedford, Lynn, and Worcester, where the Central Massachusetts Housing Alliance last week reported that the homeless count in Worcester County had climbed 20 percent in a year.

Several things changed during the pandemic that have fueled the surge, said Joyce Tavon, CEO of the Massachusetts Housing and Shelter Alliance, including increased rates of substance abuse and mental illness. But the biggest difference was the explosion of housing costs in the years that followed.

In Brockton, the median price for a single-family homehas risen nearly 50 percent in the last five years, from $339,900 in 2020 to $500,000 in 2025, according to the real estate website Redfin.While there is limited rental data for Brockton, rents in nearby Fall River rose nearly 80 percent over five years to $1,807 a month in April, according to Zillow’s Observed Rent Index. In Lowell, rents jumped 45 percent over that period, to $2,273.

That has hit low-income renters in these cities particularly hard.

“We’re talking about people whose lives are incredibly fragile, because they’re living paycheck to paycheck making just enough to support themselves or their family,” said Tavon. “All it takes is one thing to go wrong — an eviction or a medical bill — for everything to fall apart.”

The state has long targeted its 26 formally defined “gateway cities” for economic development because of their relatively affordable land and old industrial buildings that can be converted to other uses. Those goals are finally being realized due to newfound demand, and many residents have seen their downtowns transformed with shiny new apartment buildings, restaurants, and street life.

That demand is also taking a toll.

Father Bill’s & MainSpring’s new shelter/supportive housing site in Brockton. David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

Off Route 24 in Brockton, a new shelter run by the homeless nonprofit Father Bill’s & MainSpring is part of a broader housing resource center that includes permanent supportive apartments for formerly homeless people in an adjacent building. It contains 128 overnight beds and a day center with caseworkers. The new center opened last month, but it is still nowhere near enough to meet the city’s needs, said John Yazwinski, president and CEO of the nonprofit.

On a recent tour, Yazwinksi pointed out the spare cots he keeps handy in case the overnight beds fill up, which happens frequently. It can be disheartening, he said.

“To a certain extent, you will always have some amount of homelessness that’s related to mental health and addiction,” he said. “But what we’re seeing now, while those factors are certainly a part of it, is driven by the housing market.”

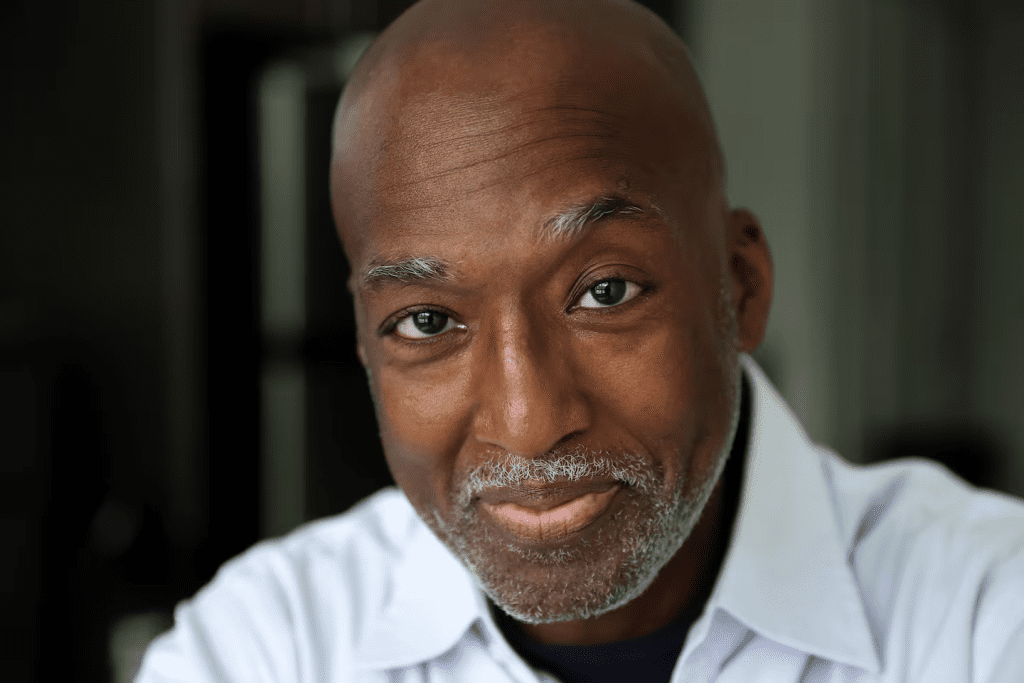

Jerome Jarrett knows too well how that can happen. Jarrett lives in a subsidized apartment with supportive services from Father Bill’s. Before that, he spent five years bouncing between shelters.

Jerome Jarrett lives in a supportive housing unit at Father Bill’s & and MainSpring new housing center, which has both shelter beds and supportive apartments. David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

Losing his job led to an eviction, and he struggled to find new work during the pandemic and a place he could afford after that.

Jerome Jarrett David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

“I have a home now, which I am very proud of,” said Jarrett, who is 57, as he sat near the window of his new, modern-looking apartment. “I also have a new perspective on how easy it is to lose something like this and end up with nothing.”

The surge in homelessness has prompted something of a municipal emergency in Brockton and places like it.

Last winter, so many tents appeared in downtown Brockton that local business owners complained to the City Council, with some saying they would have to close if the problem persisted. Howard Wright, who owns a small technology firm that was based out of a building near a popular gathering spot for homeless people, moved his business to Taunton over concerns about the safety of downtown.

“Brockton is my home,” Wright said. “But my employees don’t feel safe. I can’t expect to run a business under these circumstances.”

In November, Brockton’s City Council banned camping on public property and mandated fines for anyone who defies the ban. The council even overrode a veto from Mayor Robert Sullivan, who strongly objected to what he called the criminalization of homelessness.

Other cities, including Lowell and Fall River, have passed similar bans, while New Bedford city councilors briefly considered city-sanctioned encampments to contain people who were sleeping on the streets to specific areas.

No solution seems satisfactory. Advocates decry camping bans as inhumane, and even some business owners reject the idea.

One Gateway city trying for a middle ground is Salem, 40 miles to the north of Brockton.

City officials there passed a camping ban last year, but one that only allows encampments to be cleared when the city has shelter space available. Then they used leftover pandemic funds to open a supplementary overnight shelter downtown, which allowed them to tear down a prominent encampment near the waterfront business district.

The new Salem shelter is informal at best, run by Lifebridge out of warehouse space next to a popular thrift store that the nonprofit also runs. The tall open room full of cots gets crowded quickly, said Ethridge, the executive director, and it still feels like there are too few beds. Lifebridge is also working to expand its permanent shelter on Margin Street in downtown Salem and develop permanent supportive housing units on the same block.

It’s a temporary solution to a problem that has been long in the making, city officials said.

“Our thinking is that everyone deserves a home, and a tent is not a home,” said Salem Mayor Dominick Pangallo. “We’re starting at that point, and then thinking about creating enough housing that folks don’t need to be living in a shelter.”

To be sure, Salem is a wealthier community than Brockton, and not every city has extra money to spend on a new shelter. Father Bill’s new facility was mostly paid for with donations. But the collision of homelessness and gentrification in places like Brockton won’t be solved through charity alone.

“What we’re dealing with downtown is heartbreaking,” said Mary Waldron, executive director of Brockton’s Old Colony Planning Council, which is based in a historic building downtown. “People are struggling and we don’t want to punish them for that. But we also want to have a thriving downtown. There is no simple answer here.”

Andrew Brinker can be reached at andrew.brinker@globe.com. Follow him @andrewnbrinker.